Weather:

- Ha Noi 33oC

- Da Nang 31oC

- Ho Chi Minh 31oC

By Nguyễn Hằng

“I was desperate to draw, utterly besotted with it. In wartime, when life was hard and we were barely getting by, with my husband ill, I was caring for him and raising two children. There were times my clothes were in tatters, yet I would still put aside money to buy a metre of silk so I could paint.”

Those were the words of painter Nguyễn Thị Mộng Bích, now 94, a small, silver-haired woman, spoken on an August afternoon as she sat on the veranda of her home.

Her modest three-room house backed against a hill, its front facing a clear blue pond and, beyond the garden, luxuriant trees and the occasional birdsong in Na Village, Hiên Vân Commune in the northern province of Bắc Ninh.

The house is her retreat after a lifetime devoted to her craft, Bích is regarded as one of the foremost figures of Việt Nam’s silk-painting art.

Born in 1931 into an intellectual family in Đông Ngạc Commune of Hà Nội, she graduated from what was then called L'Ecole des Beaux-Arts de l'Indochine (the Indochina School of Fine Arts, now the Việt Nam University of Fine Arts).

From 1960, she worked as an artist at the Thái Nguyên Province’s Department of Culture.

A decade later, she returned to Hà Nội to work for the newspaper Việt Nam Độc Lập (Independent Việt Nam).

Bích was one of only a few female painters of her generation to win major awards. Her silk painting Mẹ con (Mother and Child) took first prize at the Việt Bắc Inter-Regional Department of Culture exhibition in 1961, and her work Bà già (The Elderly Woman) won first prize at the Việt Nam Fine Arts Exhibition in 1993.

Rather than pursuing the romanticised images of women popular in the colonial era, Bích cherished ordinary, everyday moments.

Her oeuvre is notable for its varied, accessible subjects, from scenes of daily meal preparations and portraits of young women in the market to the gentle, weary gaze of an elderly beggar.

Bích observed the world with the pure, tender sensibility of a woman - sincere, compassionate and unostentatious.

She is widely regarded as one of the few female artists to inherit and sustain the traditional realist style in Vietnamese silk painting.

'I craved painting'

“I loved drawing from childhood, my father was a teacher,” Bích said.

“My family had many books. When I started primary school, I was already learning French, which gave me access to many illustrated volumes in the house. I read translated works by Nguyễn Văn Vĩnh that contained beautiful illustrations, and I devoured novels by Victor Hugo and Charles Dickens."

When she came of age and joined the resistance war in the 1950s, she took part in the Cao Bắc Lạng military campaign across the mountainous provinces of Cao Bằng, Bắc Cạn and Lạng Sơn.

“What struck me was a sunset of astonishing beauty, the mountains, the clouds, the villages, and from that moment I knew I wanted to be an artist,” she said.

Additionally, her family knew many intellectuals, largely architects, which further encouraged her love of painting.

Due to the nine-year war, she did not return to Hà Nội until 1956, when she was able to continue to study fine arts.

After graduating from the intermediate course at the College of Fine Arts in 1960, Bích worked at the Thái Nguyên Department of Culture for five years, and then returned to Hà Nội for further studies.

“It was hard to earn my own living,” she said, “but I craved painting so I remained resolute in continuing. Thanks to my service in the war of resistance, I received a scholarship, though it only covered living expenses. I finally graduated with my university degree in 1970.”

Student years, she recalled, were far from carefree. Like many in the post-war years, she worked extra jobs after class while caring for her husband, a violinist, and their two sons.

After graduating she joined the abovesaid Việt Nam Độc Lập newspaper, producing illustrations, page layouts and writing on fine arts.

Bích said many of her lecturers were leading artists trained at the Indochina School of Fine Arts.

“I feel I was very lucky to learn from teachers who were both educators and practising artists so I could absorb so much from them,” Bích said.

Bích also said reading widely, including Russian books, helped develop her aesthetic sensibility and supported her creative work.

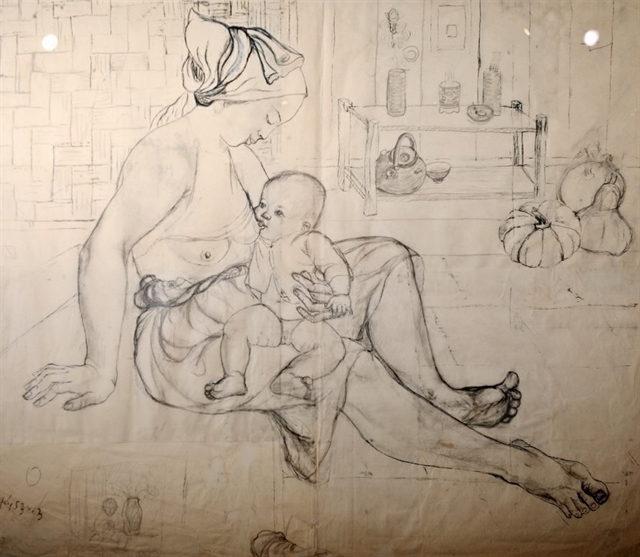

At the first national exhibition in 1960, her work Mẹ con, painted on two pieces of silk, won praise from Nguyễn Phan Chánh, an avant-garde silk painter in Việt Nam.

“He told me I was famous already,” she recalled. At school, her portrait work always received high marks from teachers.

'Never forget'

Her earliest memory dates from an excursion to the mountainous province to carry out dissemination work.

Thirsty at midday, she entered a house to ask for water and saw an old woman cradling a crying child.

When the child’s mother returned, the baby snuggled into her lap and began to feed; the posture was strikingly beautiful.

Bích made a quick sketch of the basic lines and later worked up the details from the model.

That sketch became her first silk painting, Mẹ con; she even borrowed a metre of silk from a close friend to complete it.

She invested meticulous care in the work, but it was not initially accepted into exhibitions.

Critics at the time objected to the depiction of a breastfeeding mother whose breasts were visible; it was considered inappropriate, so the painting was placed on the veranda, outside the main exhibition.

On the day, several notable artists and an academician from the Polish Academy of Fine Arts were attending.

As they passed the veranda, they saw her painting and were struck by its beauty. Silk painting was uncommon and oil was the dominant medium, but to European eyes the silk work seemed novel.

They urged the organisers to include the painting in the exhibition, and it subsequently received first prize.

“It is a memory I will never forget,” she said.

Solo exhibition

She did not hold a solo exhibition until she was 90.

“I never really thought about organising an exhibition before,” she said. “I painted for passion, simply whatever I loved, and I gave every painting my fullest attention.”

Her solo show, Walking between Two Centuries, came about by chance. Staff from the French embassy visited her home and liked what they saw; they encouraged her to exhibit.

Initially hesitant, she had relatively few works, wartime and family life had limited her output, she was nonetheless persuaded when Thierry Vergon, cultural counsellor and director of L’Espace, the French cultural centre, visited and spent four hours discussing her paintings.

When she finally agreed to hold the exhibition at L’Espace in Hà Nội in October 2020, the response was substantial. The show ran for two months, far longer than the customary week for such exhibitions, and displayed 30 works, including silk paintings, watercolours and sketches, spanning her creative journey since 1960.

Bích cherishes not only her models but the simplest objects.

“A basket, a gourd, a bunch of vegetables, a yam, a jug - I can see a soul in them. I love everything.”

In later life, unable to travel far, she watches the world close at hand. She said Việt Nam’s people and landscapes are extraordinarily beautiful.

“For me Việt Nam has four seasons of spring, summer, autumn and winter, each with its own unique beauty.”

Bích said she had not seen every corner of the country, so she told her children: “When I die, scatter my ashes at sea so I may travel everywhere and gaze on all the beauty Việt Nam holds.” VNS